I once was given advice by a senior product manager that toppled one of the fundamental assumptions I had held about the PM role. What he said was:

“Don’t go down with your products.”

I had intuitively thought of the PM as the proverbial captain who is supposed to go down with his ship (at least as far as popular opinion is concerned) but what my colleague suggested sounded more like an invitation to opportunistically hop from one product to the next, jumping ship whenever things started to look dire.

How much are we supposed to care about our products? How much of ourselves should we pour into any creative project? Should we be proud when others identify a piece of work with us personally, or should we emphasize collective ownership? And if we do that, how do we avoid the dreaded design by committee? I think it’s worth to honestly asses those questions whenever we start a new endeavor and to revisit them regularly to make sure we’re in a healthy relationship with our work as time goes on.

Me, my product, and I

Take Elon Musk as an example: Clearly, the man identifies with all of his projects to the utmost, going so far as to take personal responsibility for fixing production-line problems which is obviously not his job as CEO. He’s also publicly perceived as the face of all of his companies—consider how few news stories are able to mention Tesla, SpaceX, or SolarCity without also commenting on their charismatic leader.

Most CEOs take a different approach, hiding behind their organizations rather than wanting to be publicly identified with them 100 percent: Or would yo be able to name the CEOs of Walmart, BMW, or Volkswagen without googling?

Taking a “Musk-like” stance—one I’ll call extreme attachment—poses significant risks, such as a high chance of burn-out as well as the possibility of alienating others who want to contribute. When I was working on my first large-scale software project a few years ago I didn’t spend any time considering how much attachment to the project would be desirable. Instead, I plunged into an unhealthy relationship with my work, which ended badly for everyone involved—particularly myself.

Extreme attachment

At the time I was given a lot of responsibility at a young age: I was allowed to re-architect a large, business-critical software system and enjoyed great freedom in terms of the technologies we would use. Of course I thought I knew exactly what I was doing, even though I clearly didn’t. I jumped headfirst into the job, bursting with excitement, working nights and weekends. I greatly enjoyed the success at first—brief as it was—and took pride in the praise people heaped upon the project. But here’s the problem: I had identified so much with the product that I misinterpreted that praise not as praise for the product, which had been a team effort after all, but as praise for myself.

You can surely guess what happened next: My luck turned, the product started acting up, and customers’ complaints grew ever louder. Suddenly I was torn between crisis meetings, emergency bug fixes, and defending earlier architectural decisions to a growing number of critics. I now know that many of them where right to point out flaws in my original design and to bring up ideas for improvements but I had become so entangled in my defensive strategies that I was deaf even to the most helpful voices.

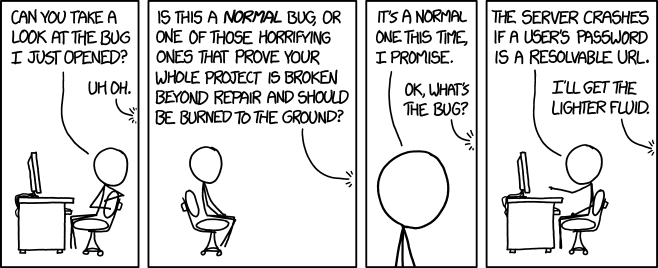

This is exactly the kind of bugs we regularly faced at my first large-scale software project.

The problem was that I had become over-identified with the product: Instead of accepting justified criticism for what it was I interpreted it as criticism of me as a person. Needless to say that this state of affairs couldn’t continue. Before wearing myself completely out I made the only choice that seemed reasonable at the time: I quit.

Extreme attachment clearly isn’t healthy or desirable for most people in most jobs. Unless you’re Elon Musk (and maybe even if you are), you should aim to put some distance between you as a person and the outcome of your work. So what’s the alternative?

Extreme detachment

On the other end of the attachment/detachment spectrum lies extreme detachment. Employees in that state have stopped caring about the what and why of their work, reducing themselves to mere recipients of orders which they then follow half-heartedly.

However appealing an army of unquestioning, interchangeable worker-bees may sound to some managers, it’s not a recipe for long-term success. Detached employees are not only unproductive, they’re also unsatisfied with their work-life and thus unlikely to stay with the company for long. In Drive, Daniel Pink points out three main factors for work satisfaction: autonomy, mastery, and purpose. If employees feel they have enough self-determination, that they are good at what they’re doing, and that what they do has a positive impact, they are generally satisfied with their work-life. Clearly, the detached employee rates low on all three factors.

One theory for how extreme detachment is created is that of bullshit jobs, popularized by David Graeber. Graeber observed that an increasing number of employees perform jobs that don’t create value but are being done nonetheless. For example, many office clerks today do things that could easily be automated, or that only need to be done because of systemic problems in organizational structure or processes and could thus be eliminated. Those types of jobs rank low on all three of the work-satisfaction factors Pink identified—autonomy, mastery, and purpose—thus people doing those jobs turn out quite unhappy.

Clearly, neither extreme attachment nor extreme detachment are desirable attitude if we want to enjoy long-term success as a company, and high satisfaction with our work as individuals. But is there an attainable middle ground?

Non-attachment

The term non-attachment is frequently used in Buddhist philosophy to denote a state of mind in which we’re neither clinging tightly, nor are we indifferent. This works for a lot of things, such as relationships, emotions, and our egos. But the easiest way to think about that concept is by looking at how we relate to physical items we own, such as our beloved electronic gadgets.

People who are overly attached to their phones for example easily turn into slaves of their electronic companions. Their primary worry before leaving the house is if their phone has enough battery to make it through the remaining day. They immediately react to every incoming notification and compulsively check their phones even when they’re not chirping and beeping. Or they engage in online flame-wars defending Apple vs. Samsung (or vice versa), cultivating emotions of anger, hatred, and bitterness that ultimately benefit nobody.

“Non-attachment doesn’t mean we don’t own things. It means we don’t allow things to own us.”

Being non-attached to our gadgets doesn’t force us to refute all modern technologies. We don’t need to adopt an ascetic lifestyle devoid of all technological amenities the 21st century offers. It rather means making sure that we get positive value from our gadgets without letting them dictate how we run our our life. It also requires us to put a healthy emotional distance between us and our possessions so that we’re not completely devastated if we lose them or they stop working.

When we’re non-attached to our work, it is also easier to deal with the inevitability of the end-of-life of our products and projects. Just like it doesn’t make sense to stick with a gadget that has reached the end of its usefulness we also need to come to terms with the fact that products have life-cycles which come to an end at some point. Emotional attachment, clinging, and denial are not only unhealthy at that stage, they also cloud our judgement about what the best way to move forward would be.

Conclusion

Neither extreme attachment nor extreme detachment are desirable if we want to build great products and enjoy satisfying professional lives. Non-attachment may be a hard to reach middle ground, but one that’s worth aspiring to. The initial question about “going down with one’s products” is still a tricky one, but from a non-attached standpoint we can think about it more clearly, without the emotional attachment that makes level-headed decisions impossible.