If you’re reading this, the mounting news of apparent breakthroughs in generative AI have surely not passed you by: Tools that can compose music, write code, paint pictures, and genuinely seem to be smart enough to pass various state exams have become publicly (and mostly freely) available in a surprisingly short timespan.

This wave of commoditization has also shed the light of public discourse onto debates about AI safety which had, until now, been confined to relatively small, mostly academic circles. A TIME magazine cover story referred to big tech’s sudden rush to bring these technologies to the market as an “AI arms race”. Valid concerns about security, safety, privacy, and ethics, the authors warn, might quickly be thrown overboard in the interest of growth in shareholder value.

So, is it possible that those advances we’ve come to witness will pave the way for something akin to “general” intelligence any time soon? And if yes, are we really headed for the singularity, a self-reinforcing “intelligence explosion” as Nick Bostrom calls it, that will leapfrog the abilities of our own monkey minds? Will our new, silicon-based overlords then feel benevolent or vengeful, compassionate or angry, supportive or murderous towards us, their creators? Or will they be as agnostic to our wellbeing as we are in our handling of “inferior” life forms whenever they come between us and our goals? Will they, in other words, pay as much attention to the interests of humanity as we would to the livelihood of an ant colony that happens to be located on the site of an “important” construction project? Or will we, eventually, merge our minds with those of the machines? Will we upload our consciousnesses into the cloud and achieve glorious immortality in the form of human-machine cyborgs, roaming the physical and / or virtual realms for all eternity?

The problem with these questions, important and fascinating as they are, is that they deal with a very different category of AI from the one we now see applied in chatbots and search engines. What we’re witnessing today are nothing more (but also nothing less) than immensely powerful generative language models. These have been trained on vast amounts of data, but regardless of what they might try to “tell” us, they are neither intelligent nor sentient. They are, however, a perfect example of the “zombie hypothesis” which had until now been merely a philosophical thought experiment.

Imagine a being that acts just like a person, responds intelligibly to everything you can ask of it, and, if prompted, claims that it is conscious. But which is, in fact, nothing more than an automata of which we definitely know that it lacks an “inner” experience. “Is such a being even conceivable?" is a philosophical question that has been debated quite heatedly in the past. Is it possible to convincingly act conscious, but, in fact, be as dark inside as a stone or a piece of wood?

What the latest achievements in generative AI have done is to unleash something onto the world that comes very close to these “philosophical zombies”. Therefore, the question of conceivability can be considered settled: There’s no doubt about ChatGPT eventually passing even advanced versions of the Turing Test. Even today, conversing with it often “feels” like talking to another sentient being. But it’s important to distinguish the machine’s ability to appear intelligent—that is to generate an output which seems thoughtful and “real”—from “being” intelligent or even conscious on the inside. It is therefore besides the point to muse whether Bing is plotting to kill you, or if its ChatGPT-based core is suffering from schizophrenia.

What’s much more concerning to me however, is the “generative” aspect of generative AI: It’s not the digital zombies producing all that wonderful content that I’m worried about. It’s the analog ones that we might turn ourselves into if we continue to clog our minds with more and more of their output.

I’ve argued that the sheer amount of content that’s constantly competing for our limited attention has already become completely overwhelming. Prioritizing, triaging, and saying “no” to most of what’s available—even if it’s undisputedly of high quality—is an essential skill if we want to make space in our busy days for moments of silence, reflection, and the deep kind of thinking that I consider a prerequisite for creative ideas to flourish. Yes, you can probably prompt ChatGPT for a futuristic vampire romance novel which is set in outer space and written in the classic style of Charles Dickens. But the result is inevitably going to be a mere recombination of existing stuff that the model had been fed beforehand. And when your mind is deeply engrossed in that computer-generated vampire love story, it’s definitely not doing any of those things it’s uniquely capable of: Creating something truly, categorically, ingeniously new; Sharing a moment of kindness with the person next to you; Or experiencing love or compassion for another real human being.

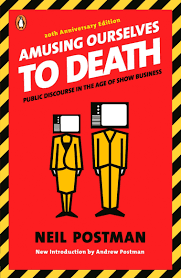

I don’t consider myself a cultural pessimist. I’m convinced that there’s a lot of value in these new technologies, if we apply them wisely. If we leverage them to augment our own, human capabilities. If we manage to use them, in the words of Steve Jobs, as a bicycle for the mind—and not merely as tools to generate more and more copy-and-paste variations of the same old things. But despite my general optimism that we will find clever ways to do that, I also see the potential for a future in which we’re collectively engaging in what Neil Postman famously called “amusing ourselves to death”. Needless to say, a combination of economic interests and AI-generated content will play a significant role in that darker vision of what might be on the horizon.

I find it almost funny that the biggest public concern with AI—that of the non-generative kind at least—had, for a long time, been its potential to power “Orwellian” use cases of perpetual and ubiquitous state-sponsored surveillance. And I should know about that kind of fear, as I’ve written an entire novel about what might go wrong in such a scenario. But the technologies that have erupted most recently point to a very different type of an equally “Orwellian” reality: Not only does 1984 put the reader in a dystopian environment where the government is using technology to spy on its citizens 24/7. In a passage that’s much less prominent, Orwell also introduces us to the versificator machines employed by the Ministry of Truth. Their purpose? Churning out endless recombinations of cheap content in order to keep the proles, those at the lowest rank of society, perpetually entertained as well as diverted—and thus to restrain their ability to harbor revolutionary thoughts.